journey to the heart of an ocean of sound

Initially, as a particular field in sound production, field recording was the result of a scientific and technological approach aimed at collecting the sounds of the world before becoming an aesthetic and artistic practice that started to use these very sounds as creative material. Over time, both approaches have reintroduced the noises of the world at the centre of creation. The publication of Field Recordings, l’usage sonore du monde (field recordings, the sonic use of the world) by Le Mot et le Reste editions was an opportunity to reflect upon what it has been customary to call (since the birth of Musique Concrete in the 50s, ambient music in the 70’s, hip hop and the appearance of the sampler in the 90s) the “Art of Field Recording”.

The Field Recording practice, as literally “recording in a field” appeared at the end of the 19th century thanks to the implementation of the first operational and portable sound recording devices. The major names in contemporary Field Recording – Chris Watson (former-Cabaret Voltaire), Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere), the Touch label, Yann Paranthoën, Henri Pousseur, Lionel Marchetti or the late Luc Ferrari – are, and were, the heirs of emblematic pioneers such as Nicolas Bouvier, a Swiss writer, photographer, iconographer and traveller.

Equipped with his antiquated Nagra, one of the first tape recorders invented by Stefan Kudelski, throughout his life Bouvier explored the world’s roads, especially in Iran and Pakistan. He notably recorded Persians and Gypsies instruments and vocals in the Middle East. As such, he belongs to this category of travelling researchers, anthropologists, sociologists, audio-naturalists and ethnomusicologists, scientific and music lovers, who recorded sounds for heritage archiving purposed, forever curious, struggling against oblivion and ignorance.

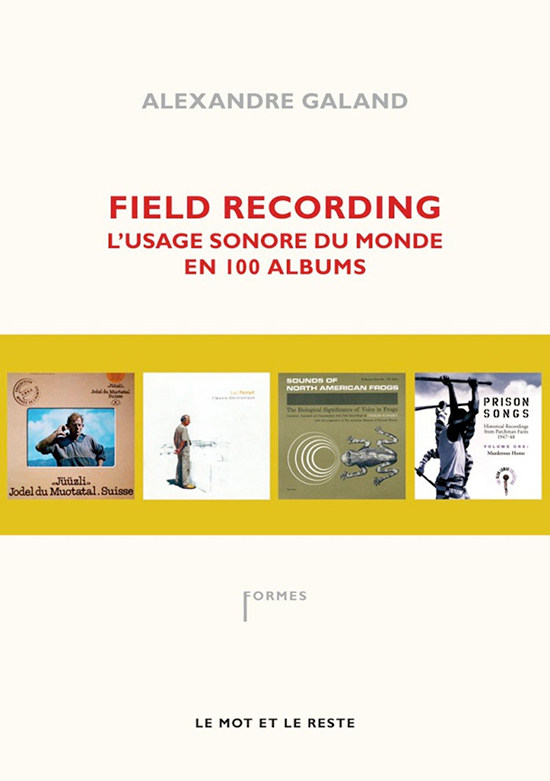

Some researchers are passionate about the singing of the lyre bird in Australia others about the melodies of the Solomon Islanders, whilst others still are focusing on the noise of the city or the exalted complaints of prisoners from North American jails. From the outset, Field Recording was as extensive operating area which consisted in rich and varied challenges and purposes. On this subject, the book by Alexander Galand, Field Recordings, l’usage sonore du monde en 100 albums (field recordings, the sonic use of the world through 100 albums), is a well of knowledge. The author – rightly – insists on the scientific/artistic dichotomy, which turns out to be complementary over time. Comprising a long historiographical essay, three interviews (Jean C. Roché, Bernard Lortat Jacob and Peter Cusack) and a solid discography, this book is a first of his kind in French and an excellent introduction for the amateur wishing to dive into this ocean of sounds.

The technical origins of an art practice

Whether it be sound techniques or studies, collections used as archives or testimony of the anthropological heritage, initially field recording specifically used a scientific approach. In the beginning at least, the practice of field recording involved an important part of research: whether to investigate the nature of sounds, to collect sound curiosities or more specifically to test new techniques and recording equipment. From this point of view, these techniques and their evolution obviously had a lot to do with the birth of an art which was yet to rise at the time.

In 1876 Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, managing to transform the sound into an electrical signal. A year later, Thomas Edison was declared to be the “inventor of the phonograph” (although in reality he was just quicker at filing a patent of his in invention than his French competitor Charles Cros). This major invention marked the beginning of an era where reproduction of natural sounds (even as a series) had become possible. The phonograph was the first device to play sounds. Users then spoke into a metal horn, while operating a needle which engraved the pattern of the waves caused thereby onto a rotating cylinder covered with a sheet of tin that could then be payed back. This did not prove very malleable and was quickly replaced by a wax film.

Finally the acetate appeared and was used with the gramophone of Emile Berliner, inventor of the process. Nevertheless, Industrial production was laborious and only truly started in 1889. For his part, the Danish Valdemar Poulsen, following the discoveries of the German Heinrich Hertz on electromagnetic waves in 1887, invented a form of magnetic recording on a flexible wire in 1898. But the German chemical company BASF managed to store sounds on a “wire” recorder from 1930. This technique improved with the advent of the pre-magnetised tape provided by the same company (which incidentally was to be used a lot by the Nazi regime).

From Field Recordings to the soundscape

As we can see, since its inception, the art of Field Recording has relied on the constant technological evolution. The “audio-naturalists,” (name then given to the pioneers who practiced this type of research), could only use the available means, always seeking higher quality, portability and accessibility. This singled out several categories of practices and several approaches within Field Recording.

Some practitioners opted for rough, in situ, audio recordings in nature, choosing not to exclude “parasite sounds” and other natural sounds that surrounded the subject and observer. This is a well known problem faced by lovers of songs and animal sounds, as well as those who record and archive ethnographic sounds (the “natives” of various regions of the world, prisoners’ songs, sailors, bluesmen, folk songs and instruments) or naturalistic sounds.

Such a problem is inherent to the sound environment induces different approaches. Some prefer to isolate the recorded object, which requires access to a studio. This is where electroacoustics and sound processing come in. With the widespread production and reproduction tools (the gramophone, the phonograph and then the tape recorder) came the era of the acoustic, electroacoustic and acousmatic experience. The initial and basic field recording turned into “acoustic ecology”, “landscape of sounds”, “cinema for the ear” or “microphony”, sometimes reproduced and “tweaked” in the studio. With the rise and accessibility of the home studio, these practices started spreading and gaining importance. Technically, everything is good to turn the world into an ocean sounds. The art of Field Recording is a quasi-infinite audio exploration of the world.

Soundind the world

The Field Recording practice really took a different turn in the 50s. In the footsteps of the great discoveries of contemporary music: from Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern’s serialism to Musique Concrète, conceptualised by the French Pierre Schaeffer and electronic music as represented by the German Karlheinz Stockhausen, the approach evolved. In this regard, it is important to note the fundamental theoretical contribution of Pierre Schaeffer and Musique Concrète to the aesthetic and creative evolution and approach taken by Field Recording. If music history is inevitably linked to the history of technology, then Pierre Schaeffer was a true pioneer.

From 1948, the French man founded the Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrete. It started as a simple radio recording studio but then actively took part in the development of a new form of music: a “concrete” music which he later renamed “electroacoustic” music. Schaeffer was one of the first to dare to master the art of manipulating sounds with the emerging technology of the early tape recorders. After much trial and error, he elaborated a theory that involved challenging the notions of “music”, listening, timbre and sound. He wrote these ideas in his Traité des objets musicaux (treatise on musical objects), in 1966. Following the lessons taught in this clear and founding text, composers started to try new experiences.

In the domain of Field Recording another French composer, Luc Ferrari, stood out even more, using the electroacoustic manipulation of sound and recordings and calling it “anecdotal” because their mundane and daily life qualities. With Schaeffer, Ferrari and later other composers like Michel Chion or Lionel Marchetti, it is indeed truly the sounds of the world, of the whole world, urban sounds, domestic sounds, tiny or supposedly “uninteresting” sounds that entered the scope of musical creation.

Field Recording and sample art: an aesthetic (r)evolution

Today more than ever, the Field Recording practice is at the heart of sound creation. From the ambient music invented in the ’70s by Brian Eno to techno and via experimental projects by various artists and musicians from the above-mentioned scenes, the Field Recording practice responds to a multiplicity of genres, approaches and trends. Ambient music, for example, was conceptualised by chance by the British musician Brian Eno when lying in bed he played an LP at the wrong speed.This micro-event was to give him the idea of an “ambient” or “wallpaper” music, which initially did not meet any of the (admittedly very free) requirements of Field Recording. It was techno musicians such as the English of The Orb, or the more industrial Cabaret Voltaire, 23 Skidoo and other bands who blended together relatively slow rhythms with sound recordings, dialogues, sounds of wind and waves for some or urban cacophony and information flows for others.

The emergence of noise in pop music, which dates back to the Beatles and the Beach Boys, became widespread through techno. In the 90s, artists from this scene were inspired both by Schaeffer’s Musique Concrète and urban or natural soundscapes from the ambient music forefathers to create their own sonic universe. This is the case for Geir Jenssen (aka Biosphere) who with a handful of truly unforgettable albums set up the basis for a unique genre, almost single-handedly creating a music school. In addition, former artists from the industrial or techno scenes, such as former-Cabaret Voltaire’s Chris Watson fully embraced this art-form, quickly making a name for themselves in this marginal field. Meanwhile, numerous major artists have tried this genre, providing the listener with pure Field Recordings records as is the case with Moondog, Yann Paranthoën, Jana Winderen or Peter Cusack. They, too, followed the footsteps of great pioneers such as Luc Ferrari, Henri Pousseur, Steve Reich or Alvin Lucier.

From its worldview, its freedom, the multiplicity of its related practices, the ongoing active evolution of means of recording the world around us, exploring “micro” and “infra” sounds, the different goals pursued by artists specialised in it, Field Recording still has a bright future ahead. Like the productions it offers, it continues to be a window looking out onto the world and creation.

Maxence Grugier

published in MCD #70, “Echo / System : music and sound art”, march / may 2013